Pinnípedos Antárticos: Las 6 especies de focas de la Antártida

Among the stars of the Antarctic wildlife show are those whiskered, flippered, dewy-eyed seals that draw oohs and aahs from the rookery beaches of South Georgia to the ice floes of the Weddell Sea.

The pinnipeds of Antarctica are composed of five species of “true seals,” aka the earless seals of the phocid family, and one eared seal. Some are definitely more commonly seen by Antarctic tourists than others, but travelers in this realm—one of the most productive marine ecosystems on Earth—certainly have an excellent chance of seeing one or more species.

The Ice Seals

The following four true seals of Antarctica are closely associated with sea ice, breeding on both pack-ice and fast-ice in late spring and early summer and hauling out on ice year-round. Each has a circumpolar distribution in Antarctica.

Leopard Seal (Hydrurga leptonyx)

The leopard seal is probably the most unique Antarctic seal. It only looks marginally like a pinniped, really; its elongated body, heavyset head, and broad, massive, toothy jaws give it more of a reptilian aura. The species gets its common name from its spotting, but the big-cat association also works when it comes to this seal’s predatory nature.

After the southern elephant seal, leopard seals are the second-largest of Antarctica’s seals (and the third-largest in the world, behind the southern and northern elephant seals). Unusually among pinnipeds, female leopard seals are larger than males—sometimes twice as large, in fact. A big female may exceed 1,000 pounds and measure more than 11 feet long.

Leopard seals prey on a variety of other organisms, from krill (very important for juveniles, and also fed upon by adults, especially in winter) and fish (such as Antarctic silverfish) to penguins and other marine mammals. They especially target pups of other ice seals—freshly weaned crabeater seals, for example, are major prey items in December and January—and sometimes take small or weakened adult seals, including Antarctic fur seals.

The teeth of leopard seals reflect this wide-ranging diet, with interlocking, trident-shaped molars for seizing krill and robust canines for dispatching bigger prey. While attacks on humans are very rare, leopard seals are potentially dangerous, and scuba-diving scientists in Antarctica give it plenty of respect and elbow room.

Mainly solitary beasts, leopard seals in some parts of the Antarctic seem to range north in winter with the expansion of the sea ice. Hauling out year-round at South Georgia, they also stray farther north, appearing as vagrants on South African beaches and seasonally foraging in Tasmanian waters. Recent evidence suggests leopard seals may actually breed in southern South America and New Zealand.

Ross Seal (Ommatophoca rossii)

The blunt-nosed Ross seal is on the smaller side for Antarctic pinnipeds, generally reaching five to eight feet long and weighing several hundred pounds. Dark-backed with a pale underside, this seal has notably large eyes—probably a reflection of its decently deep midwater foraging habits—and stubby jaws full of needle-like teeth. It’s named for James Clark Ross, whose expedition into what became known as the Ross Sea aboard the Erebus y Terror made the first description of this seal in 1841.

The biology of the Ross seal is only partly understood. They were once thought to favor the thickest parts of the ice pack, but research suggests these seals actually spend large chunks of the year hunting out in the open waters of the Southern Ocean, returning southward to the ice during the spring-summer breeding and molting window.

What are they hunting? Ross seals mostly feed on squid—hence those needle teeth—while consuming lesser amounts of fish and crustaceans.

Weddell Seal (Leptonychotes weddellii)

Weddell seals rank among the biggest of Antarctic seals, weighing between 800 and 1,300 pounds or so. They may exceed 10 feet in length, but their heads are proportionately small. Their coats are a mottled black and gray.

The species is named for James Weddell, the sealer who, in early 1823, reached farther south than any person before him, in the Antarctic sea that came to be named for him.

This seal rarely ventures far from fast-ice (sea ice anchored to bedrock or the coastline) and adjacent pack-ice, often remaining fairly close to its breeding haul-out zones throughout the year. Under the ice, it preys mainly on fish such as the Antarctic silverfish, but will also scarf squid and crustaceans, returning to breathing holes.

Crabeater Seal (Lobodon carcinophaga)

The blonde, brown, or silvery crabeater seal is not only the most abundant (and one of the most commonly seen) of all Antarctic seals, but—with a population reckoned at possibly in the tens of millions—is likely the most numerous of all large mammals on Earth aside from humans. It’s a devoted pack-ice inhabitant, its range spreading north and contracting south with the seasonal expansion and recession, respectively, of Antarctic sea ice.

This slender, medium-sized seal, usually on the order of seven or eight feet long and weighing 400 to 600 pounds, has an exceedingly misleading common name. Rather than munch crabs, it’s a krill specialist, sieving out the crustaceans with heavily cusped, tightly locking teeth. Exploiting such a prolific food source so low on the trophic pyramid is a major reason why the crabeater seal is so abundant.

Many crabeater seals bear the visible scars of past attacks by leopard seals, which prey heavily on the pups and juveniles of this species. It’s thought that a majority of crabeater pups each year are eaten by leopard seals, so adults have survived something of a gauntlet of fire. Full-grown crabeaters remain at risk from orcas.

The mummified carcasses of long-dead crabeater seals in the McMurdo Dry Valleys attest to the species’s habit of occasionally humping along inland, for reasons not at all clear.

The Southern Elephant Seal (Mirounga leonina)

The other true seal of the Antarctic is not an ice seal, and is rarely found near the pack ice. This is the southern elephant seal, the titan among pinnipeds and the biggest member of the mammalian Order Carnivora. In one of the animal world’s most extreme examples of sexual dimorphism, bull southern elephant seals are massively larger than cows (and a fair amount bigger than males of the northern elephant seal, found in the Northeast Pacific). A bull killed on South Georgia in 1912 measured 22.5 feet long and may have weighed on the order of 11,000 pounds.

Southern elephant seals are most visible when congregating in their raucous breeding rookeries, mainly found on such sub-Antarctic islands as South Georgia (where about half the world’s population breeds), the Kerguelens, Macquarie Island, and Heard Island; colonies are also found in the Falklands and, in a rare mainland setting, on the Valdes Peninsula of Argentina. Spring breeding season includes sometimes-bloody battles between those gargantuan bulls fighting over the harem rights accorded a victorious “beachmaster.”

Those same islands see elephant-seal haulouts in summer for molting purposes, though a few males will also molt on the Antarctic coast.

For all the drama of those breeding battles on sand and cobble beaches, southern elephant seals spend most of their year alone, out in the open ocean. They journey long distances to forage in Antarctic waters, with bulls in particular often hunting along the continental shelf. That foraging goes down at impressive depths, as southern elephant seals are among the champion divers of marine mammals, capable of descending well past 3,000 feet. They’re mainly pursuing squid down there, plus such fish as Antarctic cod and lanternfishes.

Those cruising to South Georgia as part of an Antarctica itinerary will likely find the huge, hauled-out elephant seals one of the standout sights of their entire trip.

The Eared Seal of the Antarctic: the Antarctic Fur Seal (Arctocephalus gazella)

The Antarctic fur seal is more closely related to sea lion—fellow eared seals—than the phocids, possessing an external ear flap, large foreflippers, and much greater mobility on land than those more sausage-like true seals. A dense pelt, rather than blubber, keeps fur seals warm in the chilly waters they favor.

This is the smallest of the Antarctic seals: Females weigh around 90 pounds or so, while males may weigh more than 400 pounds.

Antarctic fur seals share much of the range of the southern elephant seal. They typically breed on sub-Antarctic islands—by far the majority of the global population on South Georgia—and mainly south of the Antarctic Polar Front, though a few rookeries exist north of it. (On Macquarie Island north of the Front, Antarctic fur seals rub shoulders with two close relatives: the Subantarctic and New Zealand fur seals.)

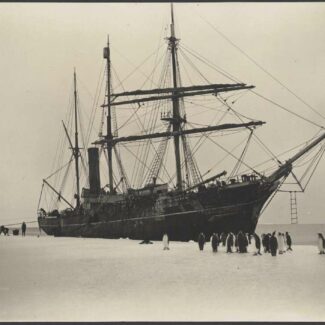

Antarctic Sealing History

Some of the earliest and widest-ranging of Antarctica’s explorers were actually sealers, who plundered these bottom-of-the-world waters along with whalers. Commercial sealing got underway on South Georgia as early as the late 1700s, with heavy harvesting of southern elephant seals (prized for oil) and Antarctic fur seals (prized for their pelts). By the early decades of the 19th century, sealing voyages were penetrating ever farther southward into the Antarctic in quest of seals.

Major reductions in pinniped numbers in the region followed. Fortunately, in 1972 the Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Seals was signed under the mantle of the Antarctic Treaty, placing robust protections on all six of the seal species in the Southern Ocean south of 60 degrees latitude. Numbers of such heavily impacted species as the Antarctic fur seal have been recovering since the wanton overhunting of past centuries.

Descargo de responsabilidad

Nuestras guías de viaje tienen únicamente fines informativos. Si bien nuestro objetivo es proporcionar información precisa y actualizada, Antarctica Cruises no hace ninguna representación en cuanto a la exactitud o integridad de cualquier información en nuestras guías o encontrado siguiendo cualquier enlace en este sitio.

Antarctica Cruises no puede y no aceptará responsabilidad por cualquier omisión o inexactitud, o por cualquier consecuencia derivada de ello, incluyendo cualquier pérdida, lesión o daño resultante de la visualización o uso de esta información.