Cómo se llamaron la Antártida, sus islas y lugares

Most corners of the globe boast indigenous names for landmarks, or many, many centuries of names imposed by colonizing and occupying cultures. Antarctica, which lacks a native human population, has no such geographic heritage. Names weren’t applied to specific places on the White Continent until the first half of the 19th century. And Antarctica doesn’t have true permanent residents, given its year-round research stations and bases operate with a rotating staff on comparatively short-term stints.

“Despite these unusual characteristics,” notes the U.S. Geological Survey (one of numerous national agencies which contribute to the modern naming of Antarctic features), “application of names to geographic features is an inherently human need, deriving from our desire to make a landscape familiar so that our place-based activities can be conducted more efficiently. Antarctica is no exception and so there is a legitimate need for mechanisms to propose, review, and approve names of geographic features.”

And because there’s much yet to explore in Antarctica, and because of the wide-ranging scientific investigations underway at the bottom of the world every year, the process of naming features on this frozen continent continues apace.

In this article, we’ll delve into the history and process of placenames—more fancily termed toponyms—in Antarctica. We’ll also highlight numerous examples—mainly, though not exclusively, names of islands and coastal features, on account we’ve got separate, dedicated blogposts focused on a range of specific landmarks and other aspects of the White Continent’s geography—from glaciers, ice shelves, and mountains to research stations—which at least partly address their nomenclature.

To begin, though, we’re going to tackle the placename of all placenames when it comes to the bottom of the world: Antártida itself.

The Etymology of Antarctica

Antarctica has sort of a ghostly pseudo former name, in that the spirit of Terra Australis—Latin for “Southern Land”—hangs over its icy vastness. The Roman scholar Cicero is credited with the first usage of that moniker for a hypothetical southern continent that, early geographers believed, had to exist to balance out all of the northern landmasses.

Yet up until the early 1800s, nobody had seen this alleged Southern Land, even as explorers and mariners had increasingly forayed along the southern fringes of the Southern Hemisphere’s known continents. In 1814—with Antarctica as yet undiscovered—the British cartographer Matthew Flinders suggested a derivation of Terra Australis, Australia, as the name for the “Down Under” continent that, up till then, had primarily been called New Holland (bestowed by a Dutch explorer in the 17th century).

Flinders’ proposed renaming of New Holland as Australia was formalized a mere four years after the Antarctic mainland had finally been sighted: in January 1820, by Admiral Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen). That’s pretty crazy timing: But for Flinders’ proposal just a few years before the White Continent was discovered, it may have been named Terra Australis—or perhaps even Australia!

It took until 1890 for this huge polar continent to officially earn the name Antarctica, thanks to the Scottish mapmaker John George Bartholomew. But that name has more ancient roots. It’s a Latinization of a Greek word first coined by Marinos of Tyre: Antarktikos, which means “opposite the Arctic.”

The Ancient Greeks applied the label Arktikos, aka Arctic, to the Far North because of a constellation they called Arktos, which means “bear,” and which we know today as Ursa Major (which contains the familiar Big Dipper). Ursa Major is a circumpolar constellation known for pointing to Polaris, the North Star: hence the association made by Greek geographers via Arktos, the North, i.e. “the Land of the Bear.”

Thus Antarctica (from Antarktikos), while meaning “opposite the Arctic,” could more literally be translated as “opposite the Land of the Bear.” And that’s got kind of a poetic truth to it, given the polar bear (which, mind you, the Ancient Greeks didn’t know about it) embodies the bear/North connection in reality, resting at the top of the Arctic food chain—and there are no bears (or any other land mammals) on the opposing southern continent of Antarctica.

History of Antarctic Placenames

Legitimate Antarctic toponymy (the naming of places) basically dates back to 1819, when the British captain William Smith discovered the South Shetland Islands: the first landmass identified south of the Antarctic Circle.

We ought, however, to give some credit to the famous British Royal Navy explorer James Cook, as he named the Sub-Antarctic islands of South Georgia (for King George III) and the South Sandwich Islands (for John Montagu, head of the Royal Navy and 4th Earl of Sandwich). (Cook, the first to cross the Antarctic Circle, also used the phrase “Southern Ocean,” which in recent decades has become increasingly recognized as an official label for the ocean girdling Antarctica.)

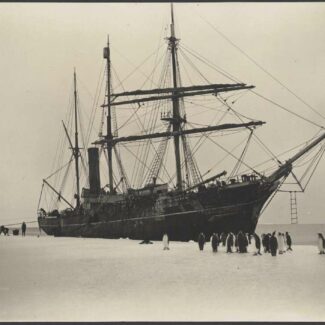

Many early Antarctic explorers applied placenames freely: honoring royalty or expedition patrons back home, honoring their own intrepid vessels, waxing poetic about tempestuous seas and shapely mountain peaks.

But what can be termed the “discovery period” of Antarctica also involved commercial sealing and whaling operations lured ever southward in quest of unexploited stocks of pinnipeds and baleen whales. While many Antarctic placenames were coined by these fleets, sealers in particular were not always eager to publicize their farflung hunting grounds for fear of competition, so some geographic features surely known to (and maybe even informally named by) these commercial vessels weren’t formally labeled until later.

Between the territorial claims of nations such as France, the U.K., Norway, and Argentina and the profusion of scientific explorations and adventuring by numerous other countries, Antarctic placenames began piling up in the 20th century.

Antarctic Naming Bodies

Many of the signatories of the 1959 Antarctic Treaty have their own national agencies or committees designated to oversee placenames in Antarctica. These include nations with territorial claims on the White Continent. The U.K. Antarctic Place-names Committee and Australian Antarctic Division Place Names Committee, for example, approve toponyms for their respective territories. But Antarctic placenames are also formalized by countries without such claims; the U.S. Board of Geographic Names, for example, has a special Advisory Committee on Antarctic Names (ACAN).

Numerous national committees focused on Antarctic placenames allow for anybody to propose new or renamed toponyms. There are, naturally, certain criteria to be met: The New Zealand Geographic Board/Ngā Pou Taunaha o Aotearoa, which concerns itself with placenames in Antarctica’s Ross Dependency, clearly defines what it considers acceptable and unacceptable names for Antarctic features, the latter category including everything from “derogatory, discriminatory, frivolous, offensive, or in poor taste” choices to the “names of pets.” (Sorry, Fido.)

These days, these various naming authorities coordinate with one another, and the assignment of placenames in Antarctica has for decades been coordinated by the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR), a branch of the International Council of Science. Since 1992, Antarctic placenames approved by all nations conducting activities on the White Continent have been compiled in the SCAR Composite Gazetteer of Antarctica.

In 2021, SCAR’s Standing Committee on Antarctic Geographic Information (SCAGI), which includes representatives from Antarctic Treaty nations, released standardized guidelines for Antarctic placenames, partly for the sake of consistency and to preserve historically significant or otherwise distinctive toponyms.

Antarctica Island Names & Placenames

Antarctic island names and placenames typically reflect a few basic themes: honoring people or ships, describing the appearance or conditions of a particular site, reflecting a particular activity conducted in the place, or evoking a story of moment in time—coined to mark an event, an emotion, or some other association specific to the nomenclator or “namer.”

The following is far from an exhaustive overview of Antarctic placename categories, and some categories definitely overlap. And, as we said at the outset, we’re mostly focusing here on such features as islands and coastal waterways. But the examples we’ll run through do embody some broad naming patterns that have been at play in Antarctica since the earliest days.

Commemorating People

A very large proportion of Antarctic toponyms honor people of one kind or another: from the folks bestowing the name in the first place (depending, maybe, on their level of self-regard) to sponsors of expeditions, political leaders and royals, or explorers, scientists, and other Antarctic travelers whom subsequent individuals, agencies, or committees deemed worthy of commemoration on the landscape.

The biggest of the South Shetlands, Isla del Rey Jorge, is an early case in point: named by the English explorer William Smith in 1819 for—well, King George, namely King George III, who died the next year.

Antarctica’s largest island, Alexander Island in the Bellingshausen Sea, honors Tsar Alexander I of Russia. Upon sighting the island in 1821, Admiral Bellingshausen named it “Alexander I Land,” on account he believed it was actually part of the mainland.

There are more than a few descriptive placenames in Antarctica incorporating “white”—not exactly a shocker in this polar realm. But not all “white”-named spots in Antarctica are referencing ice and snow: White Island in Sulzberger Bay was named for Dr. Paul Dudley White, a medical adviser on the U.S. Navy’s 1946-1947 Operation Highjump.

In modern times, Antarctic placenames referring to people tend to be approved in recognition of those scientists and glaciologists who’ve done important research or performed other service in Antarctica. But they may also honor individuals who’ve made valuable contributions to fields or subjects relevant to the White Continent. An example would be Attenborough Strait, between Charcot and Latady islands in the Bellingshausen Sea, a SCAR-registered name proposed by Great Britain in tribute to the great natural-history presenter Sir David Attenborough, who’s been a strong voice sounding the alarm about climate change.

However, with so many places to be named and so few candidates with direct associations to Antarctica left to consider, you’ll also find plenty of places named after people with little or no link to Antarctica at all, such as pioneers of aviation, astronomy, medicine, and photography, as well as famous composers and characters from the fictional works of Charles Dickens, Jules Verne, and Herman Melville (Moby Dick).

Commemorating Ships

Many Antarctic features are named after the ships used in the region by historical exploratory, sealing, and whaling fleets. Take Livingston Island’s Hero Bay, for example, named after the American sealing captain Nathaniel Palmer’s sloop Hero that forayed south from the South Shetlands into uncharted waters in 1820, reaching the coast of the Antarctic Peninsula.

Another of numerous examples is Puerto de Neko in Andvord Bay along the Danco Coast of Graham Land: named after a Scottish factory whaleship, the Neko, which used it as a regular anchorage from the early 1910s through the mid-1920s.

Referencing Events, Activities & Purposes

Lots of bygone stories and experiences are encoded in Antarctic toponyms. As you can imagine, many are evocative of the hardship endured in those early days of exploration, from Exasperation Inlet y Cape Disappointment, to Blow-me-down Bluff y Mirage Island. But there are a few that elicit those rare moments of elation—and relief, no doubt—too, such as Dream Island y Picnic Passage.

Many placenames here reflect strategic landmarks used as safe anchorages, supply sites, or other critical bases amid Antarctica’s vast wilderness and often-fierce weather. There’s Safety Island off East Antarctica’s Cape Daly and Refuge Island (off Graham Land’s western coast), for example. The striking name of Neck-or-Nothing Passage off Desolation Island’s Blythe Bay stems from 19th-century sealers, who used this channel to flee stormy weather. The name of Vortex Island off the Trinity Peninsula was given by an August 1945 Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey party waylaid there by a swirling blizzard.

Quite a few placenames in Antarctica explicitly link to the long-ago operations of sealers and whalers. Deception Island, a major base of operations for whalers, includes near its entrance Bahía de Whalers. In the South Orkneys, you’ll find the Flensing Islands, named for the process by which whalers remove strips of blubber from a killed whale.

More recently, in an attempt to raise awareness of global climate change issues, a series of glaciers draining the Getz Ice Shelf in West Antarctica that have been particularly adversely affected have been named after sites of important climate treaties and reports. For example, the northernmost of these glaciers, the newly named Glasgow Glacier, commemorates Glasgow as the site of the 2021 U.N. Climate Change Conference (COP26).

Descriptive Names

Taken at their broadest, descriptive names in Antarctica include those reflecting the appearance, shape, conditions, or other physical attributes of a place, and, more subjectively, a site’s atmosphere or “vibe.”

Off the western coast of Graham Land alone, for instance, there’s Tadpole Island, named for its pollywog shape; the pintsized islets called the Niblets; and the distinctively kinked inlet called Dogs Leg Fjord. Alexander Island includes the rugged formations of the Dragons Teeth, while the spiky seastacks named by whalers the Sewing-Machine Needles poke up off Deception Island.

And speaking of: Ring-shaped Isla Decepción, a flooded volcanic caldera in the South Shetlands, was so-named by the sealer Nathaniel Palmer in 1820 because of the hidden nature of its interior harbor, accessed only by a narrow entrance.

The extreme remoteness and barrenness of Antarctica—and the extreme isolation experienced by its comparatively few visitors—has inspired plenty of descriptive names down here, such as Desolation Island, Dismal Island,

Referencing Other Places

Two of the earliest clusters of tierra firme discovered south of the Antarctic Circle, meanwhile, the South Shetland y South Orkney islands, were named after similarly high-latitude (though balmier) Scottish archipelagos: the Shetlands and the Orkneys.

(Returning to the South Sandwich Islands: Captain Cook actually originally named these islands “Sandwich Land” to honor the Earl of Sandwich, and the name was modified to its present form after Cook, in 1798, named the Hawaiian Islands the “Sandwich Islands.” Thus the current name references both a person and a location, though of course Sandwich Islands for Hawaii—where Cook met his end, incidentally—is no longer used.)

El mencionado Blythe Bay along Desolation Island was likely named (around 1821) for Blyth, England: the home port of a sealing brig, the Williams.

There’s a Brooklyn Island in Antarctica, named by the Belgian Antarctic Expedition for the NYC borough one of its members, Dr. Frederick A. Cook, called home.

Evoking Myth, Fable, and Religion

Antarctica’s primal grandeur is of mythic proportion, and the scenery borders on the unreal. Thus it’s little surprise that mythological references abound in Antarctic toponymy. American sealers named the entrance to Deception Island, often wracked by strong winds, Neptune’s Bellows. In 1948, the Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey (now the British Antarctic Survey) named Damocles Point on Alexander Island because its looming ice cliffs called to mind the sword of Damocles.

Underworld placenames are in no small short supply in Antarctica. Livingston Island’s Byers Peninsula has a whole suite of them, with a rather sulfurous geography established by such features as Devils Point, Lucifer Crags, Acheron Lakey Hell Gates.

Oddball Names

Antarctica’s rich and ever-growing pantheon of placenames includes plenty of eccentric and unusual ones. The Omicron Islands and nearby Omega Island in the Palmer Archipelago off the Antarctic Peninsula nod to the Greek alphabet. Pourquoi-Pas Island gets its name from one of the 1908-1910 French Antarctic Expedition’s ships, the Puorquoi-Pas? (“Why Not?”). The moniker of Parallactic Island rather dryly reflects the taking there of parallactic measurements of the Aurora Australis (Southern Lights) in 1961. Numbat Island off the Enderby Land coast of East Antarctica—part of the enormous Australian Antarctic Territory—nods to a charming Aussie marsupial.

Commercial Names

Yes, sadly even one of the most remote and pristine places on earth is not immune from the sullied reaches of capitalism—although there is an argument to be had that it’s surprising there aren’t more commercial placenames on the White Continent considering the considerable use of (and reliance on) specialist instruments and equipment by scientists.

Mobiloil Inlet on the east side of the Antarctic Peninsula is perhaps the prime example, one of the relatively few Antarctic toponyms ultimately named after a commercial business (Australian explorer Hubert Williams named it in 1928 after one of Vacuum Oil Company’s products), and there are a handful of others that reference vehicle types or manufacturers, such as Weasel Hill, Skidoo Nunatak, Bombardier Glacier, Mount Tuckery Muskeg Gap.

Descargo de responsabilidad

Nuestras guías de viaje tienen únicamente fines informativos. Si bien nuestro objetivo es proporcionar información precisa y actualizada, Antarctica Cruises no hace ninguna representación en cuanto a la exactitud o integridad de cualquier información en nuestras guías o encontrado siguiendo cualquier enlace en este sitio.

Antarctica Cruises no puede y no aceptará responsabilidad por cualquier omisión o inexactitud, o por cualquier consecuencia derivada de ello, incluyendo cualquier pérdida, lesión o daño resultante de la visualización o uso de esta información.