The Antarctic Snow Cruiser & Other Lost Antarctic Vehicles

- The Ground-breaking Vision of the Snow Cruiser, a One-of-a-kind Antarctic Exploration Vehicle

- The Design of the Antarctica Snow Cruiser

- The Inauspicious Inaugural Journey of the Snow Cruiser

- An Uninspiring Antarctic Debut

- Abandonment

- Fate of the Antarctic Snow Cruiser

- Other Lost or Abandoned Antarctic Vehicles

- More on Antarctica Vehicles, Vessels, & Wrecks

The White Continent isn’t easy on vehicles. That’s probably pretty obvious: We’re talking an astonishingly remote polar landmass at the bottom of the world, hundreds of miles from the nearest continent, almost wholly swaddled in ice and much of it subject to brutal weather as tough on machinery as it is on human beings.

Many a motorized vehicle has been employed over the past century or so in Antarctica, from early-times motorized sledges to today’s four-wheelers, tractors, and aircraft. The challenges of the Antarctic have inspired some highly creative rigs, including some that can only be described as borderline zany.

Among vehicles used in Antarctica, there may be no more fabled one than the Snow Cruiser, legendary not only for its supersized, majorly kitted-out design but also its ignominious performance on the ground (or, shall we say, on the ice).

The Ground-breaking Vision of the Snow Cruiser, a One-of-a-kind Antarctic Exploration Vehicle

The ill-fated Antarctic Snow Cruiser was built for the 1939-1941 United States Antarctic Service Expedition, commanded by Rear Admiral Richard Byrd, who at that point had already two of his own expeditions to the White Continent. This government-financed effort, charged with establishing two farflung research bases and other ambitious goals, was partly intended to cement American presence on the White Continent as other nations—not least Nazi Germany—were increasing theirs.

The Snow Cruiser’s originator, Thomas Poulter, had been second-in-command on the second of these Byrd-led expeditions in 1934. Dire straits encountered on that journey—namely Admiral Byrd’s near-lethal carbon-monoxide poisoning at a weather station away from base camp, and the difficulty of reaching him—inspired in Poulter the idea of a mobile base, which he envisioned would be safer and more useful than the traditional stationary expedition camp.

The unveiling of the Snow Cruiser in model form at Chicago July 14, 1939 by its designer Dr. Thomas Poulter. (Photo: AP)

A rugged, weatherproof, decked-out base on (big) wheels: that was the basic concept behind the Antarctic Snow Cruiser. Poulter’s position as the scientific director of the Research Foundation of the Armour Institute of Technology (today’s Illinois Institute of Technology), and the high-stakes logistical demands of the U.S. Antarctic Service Expedition, gave him the opportunity to see his schemed-up Antarctic exploration vehicle actually constructed.

The Design of the Antarctica Snow Cruiser

It’s no stretch to call the Snow Cruiser one of the most ambitious vehicles ever actually assembled. Some 56 feet long, 19 feet wide, 16 feet high, and 37 tons fully loaded, it was a monster of a ride, possessed of pronounced overhangs at either end to contend with crevasses. Its 10-foot-tall Goodyear tires were treadless, the idea being they would thus avoid getting clogged by ice and snow. (This proved a rather fateful design.) Among the more innovative features of the Snow Cruiser were its retractable wheels, engineered not only to better traverse crevasses but also to allow engine exhaust to warm those smooth rubber tires and thereby prevent them from cracking.

A cutaway diagram of the Antarctic Snow Cruiser and diagram of the crevasse crossing technique using its retractable wheels.

The Snow Cruiser was powered by a diesel-electric drivetrain incorporating a pair of diesel engines as well as generators and electric motors, all adding up to 300 horsepower and a top speed—on pavement, anyhow—of 30 miles per hour.

Besides the engine room, the innards of this hulking machine accommodated a control cabin, quarters for four or five crew members, a machine shop, darkroom/galley, storeroom, and a berth for two spare tires, among other compartments.

Up top, the Snow Cruiser boasted a socket for a detachable derrick used for changing tires and other tasks, and—another of the vehicle’s wilder features—attachments for a biplane that, with a range of 300 miles, could be used to scout ahead for route-finding.

Building the Antarctic Snow Cruiser

Designing the Snow Cruiser took some two years, beginning in 1937. Its actual construction, though, which went down at the Pullman Company just outside Chicago, was a remarkably swift affair for such a gargantuan and complicated vehicle: It was completed—at a cost of $150,000—in a mere 11 weeks in the summer of 1939.

The Inauspicious Inaugural Journey of the Snow Cruiser

Before the Antarctic Snow Cruiser could reach the Byrd’s Little America III base on the Ross Ice Shelf, it had to get from the Chicago area to the Boston docks, more than a thousand miles away.

It made that initial journey, flanked by police escort, along the roadways of the Midwestern and Northeastern U.S., which proved more difficult than might’ve been expected for a state-of-the-art vehicle designed for polar exploration. Among other mishaps, the Snow Cruiser ended up tumbling into a creek in Ohio, which demanded a multiday extraction effort.

Ultimately, the Snow Cruiser did finally make it to Boston on November 12, 1939, though its rather harrowing, herky-jerky trip there certainly raised a few questions as to the vehicle’s “road-worthiness.”

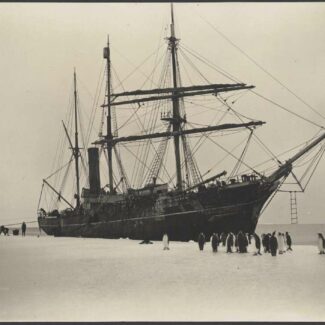

The North Star arrives in Antarctica, moored to ice in the Bay of Whales on January 15, 1940. (Photo: A.J. Carroll / United States Antarctic Service)

Loading the Antarctic Snow Cruiser onto its transport vessel, the North Star, was no easy feat, and ended up requiring the removal of the vehicle’s aft section (to be reattached in Antarctica). But bringing this one-of-a-kind machine to the White Continent proved otherwise easy enough, and on January 15, 1940, the North Star steered into the ice harbor of the Bay of Whales, ready to unload the Snow Cruiser near Little America III.

An Uninspiring Antarctic Debut

That unloading process (captured in color footage) wasn’t exactly smooth: The wooden ramp constructed for it buckled when the Snow Cruiser was only partway down, and only a rapid acceleration by Poulter, in the driver’s seat, got the supersized rig safely onto the Ross Ice Shelf.

It basically all went downhill from there. The Snow Cruiser’s treadless balloon tires quickly became mired in soft snow, and traction was only marginally improved by adding the spare tires and chains. The crew found that driving the bogged-down, underpowered Snow Cruiser in reverse was most effective, but “effective” is to be understood in relative terms. Soon enough, it was decided to convert the vehicle—deemed effectively useless for traveling—into a stationary base at Little America III.

Sergeant Felix Ferranto, radio operator, works with a primus torch to thaw out the wheel motors of the Snow Cruiser on August 23, 1940. The air temperature was -50 Fahrenheit (-45 Celsius) at the time. (Photo: C.C. Shirley / United States Antarctic Service)

And on that front, Poulter’s Snow Cruiser, failure though it unquestionably was for its intended purpose, did prove pretty useful: Its insulated interior, heated by circulating engine coolant, offered cozy working and living quarters in the severe elements of the Ross Ice Shelf.

Abandonment

With World War II looming, the efforts of the U.S. Antarctic Service Expedition soon came to an end, and the Snow Cruiser ended up abandoned at Little America III on December 22, 1940.

Expedition members marked the location of the Snow Cruiser with bamboo poles before bidding it adieu. Personnel returning to the site of Little America III sighted the vehicle in 1946. A dozen years later, another expedition only found it on account of the poles protruding above the accumulated snowpack; a bulldozer was used to unbury the Snow Cruiser, and an inspection showed it to be well-preserved, all things considered.

The Snow Cruiser buried after a 50 mph blizzard had blown through. (Photo: United States Antarctic Service)

That 1958 visit was the last time anybody saw this one-of-a-kind flop of a polar cruiser.

Fate of the Antarctic Snow Cruiser

Where exactly the Snow Cruiser is today remains one of the more fascinating mysteries in Antarctica. There was even a farfetched Cold War theory that the Soviets had retrieved it.

In fact, we have a decent idea of the Snow Cruiser’s fate, even if its exact location remains unknown.

In 1963, crew aboard the U.S. naval icebreaker, the USS Edisto, discovered an iceberg in the Ross Sea that appeared to contain, in buried, cleaved-away cross-section, remnants of the Little America III camp. The Ross Ice Shelf in the vicinity of the Bay of Whales is known for calving icebergs, and sometime in the early 1960s it appears one of these events set some or all of Little America III afloat.

Based on analysis of a Little America III map, photos, and calving dynamics along the Ross Ice Shelf, a pair of researchers, Ted Scambos and Clarence Novak, speculate that the Snow Cruiser ended up on a separate iceberg than the one the Edisto encountered: one that calved separately, or perhaps broke off the Edisto berg.

Based on how most icebergs broken off this area of the shelf behave, Scambos and Novak suggest the Snow Cruiser likely ended up dumped into the Ross Sea and now rests on the seafloor, amid other Little America III detritus, somewhere along where the ice front stood circa 1962.

Scambos and Novak published their study in 2005, when calving events had exposed that 1962-vintage ice-front location; they believed there was thus a window for searching for the sunken Snow Cruiser. As a more recent article in The Drive notes, the ice shelf subsequently re-covered these waters, but the frequency with which very large icebergs break off in this area suggests a future opportunity for scanning the seabed—and maybe even salvaging the Snow Cruiser—will arise.

Other Lost or Abandoned Antarctic Vehicles

The Snow Cruiser’s not the only abandoned Antarctic transport vehicle. For example, near McMurdo Station, visitors sometimes trek to the wreck of a Lockheed C-121 Constellation plane, the Pegasus, which was forced to crash-land there during a storm in 1970. All 80 people aboard survived. The plane—namesake of the Pegasus Field airstrip, closed in 2004 due to excessive summertime melt—is generally mostly buried in snow, though sometimes partly uncovered by curious sightseers.

The Super Constellation (C121J) aircraft “Pegasus” crashed near McMurdo Station on 8 October 1970 and can still occasionally be seen today. (Photo: Ralph Lewis)

In the 1960s, Australia’s Mawson Station famously employed an improbable car for practical transport: the Volkswagen Beetle. A number of these flashy little rides made the trip to this remote locale and performed quite well there, including the famous first Mawson Beetle: the ruby-red Antarctica 1, aka the “Red Terror.” Where Antarctica 1 ended up after its illustrious career on the White Continent, then somehow—after months of hard service amid the cold, ice, and wind of Mawson—winning the 1964 BP Rally in Australia, has been the subject of much speculation, as it fell off the radar sometime in the 1960s.

Another of the Mawson VW Beetles, nicknamed “Antarctica 4 ¼,” actually met its end down at the bottom of the world, falling through the sea ice in September 1967.

The Ruby-Red VW Beetle Antarctica 1 proved very useful for ‘around station’ jobs including transporting supplies out to field teams. (Photo: Geoff Merrill)

More on Antarctica Vehicles, Vessels, & Wrecks

Keen on more information regarding the wheeled, keeled, and winged vehicles and vessels that have aided Antarctic exploration, research, and tourism over the years? We’ve got plenty more to explore, including overviews of historical and modern Antarctic vehicles in our article on getting around on the White Continent and a survey of famous Antarctic shipwrecks.

Of course, most tourists in Antarctica see this special place from the comfort and security of expedition cruise ships. Explore our selection of Antarctic cruises below.

Disclaimer

Our travel guides are for informational purposes only. While we aim to provide accurate and up-to-date information, Antarctica Cruises makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information in our guides or found by following any link on this site.

Antarctica Cruises cannot and will not accept responsibility for any omissions or inaccuracies, or for any consequences arising therefrom, including any losses, injuries, or damages resulting from the display or use of this information.