Antarctica's 10 Most Famous Shipwrecks

- How Many Antarctica Shipwrecks Are There?

- The 10 Most Famous Shipwrecks in Antarctica

- 1. The San Telmo

- 2. The Halbrane

- 3. The Antarctic

- 4. The Fridtjof Nansen

- 5. The Dundonald

- 6. The Endurance

- 7. The Governoren

- 8. MV Explorer

- 9. MY Ady Gill

- 10. Mar Sem Fim: The Antarctica Ghost Ship

- Preservation of Antarctic Shipwrecks

- The Safety of Modern Antarctic Travel

From the notoriously tempestuous seas of the Drake Passage to the roving icebergs, shifting pack ice, stormy conditions, and sheer remoteness of the Southern Ocean, Antarctic waters have been a treacherous realm for mariners for centuries, wrecking ships since at least the 17th century, when wooden sailing vessels first began foraying into the Drake.

By the late 1700s and early 1800s, expanding maritime commerce and exploration, and the ever-questing voyages of sealers, meant more and more ships were foundering at the threshold of the Antarctic. Later in the 19th century, whalers began increasing their trade in the Southern Ocean, and thus whalecatchers and factory ships were added to the roster of storm-, ice-, and (amazingly) fire-wrecked vessels.

Since then, all sorts of vessels have been wrecked in one fashion or another in Antarctica over the years: from wooden clipper ships and fiberglass yachts, to trawlers and pontoons. Even a submarine has met its end in the region: the Argentine sub ARA Santa Fe, mortally damaged by a British helicopter near South Georgia in 1982 during the Falklands War and scuttled a few years later.

How Many Antarctica Shipwrecks Are There?

According to the Maritime Archaeology Sea Trust, better than 125 wrecks are documented in South Georgia, the South Sandwich Islands, and the Antarctic Peninsula, with the majority sealing and whaling vessels associated with operations in, and foundering near, South Georgia, the so-called “Southern Capital of Whaling”.

However it’s hard to say how many shipwrecks in total the broader Antarctic and Sub-Antarctic region harbors. More than 800 wrecks alone are thought to lie on the bottom of the Drake Passage, although it does have a longer and busier history of maritime traffic than most of the rest of the region.

The 10 Most Famous Shipwrecks in Antarctica

Here we’ll spotlight a number of the most notable examples of ships to succumb to the Southern Ocean (in chronological order), including a couple associated with some of Antarctica’s most famous survival stories.

1. The San Telmo

One of the better-known early Antarctic wrecks, the Spanish naval ship San Telmo set sail on an ill-fated voyage from Buenos Aires, Argentina, on July 9, 1819, bound for the Spanish colony of Montevideo, Uruguay. However, it never reached its destination, likely having been caught in a powerful cyclone in the Drake Passage.

She was last seen on September 2, 1819, near the easternmost point of the South Shetland Islands, off the coast of Antarctica, and thought to have sank soon after with all 644 crew members on board perishing in the frigid waters.

The fate of the San Telmo remained a mystery for many years, until 1960 when an Argentine expedition discovered the remains of a shipwreck on the coast of Livingston Island in the South Shetland Islands. While there is still debate among experts, many believe that these remains belong to the ill-fated San Telmo.

2. The Halbrane

Ok, so this is a fictional Antarctic shipwreck but we thought we’d include it in our list given its renown! First published on 1 January 1897, Jules Verne’s science-fiction novel An Antarctic Mystery was an unofficial sequel to Edgar Allan Poe’s only novel, 1838’s “The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket”. The protagonist, Mr.Jeorling, believing that book to be factual, goes in search of the fictional Mr. Pym, as far as the sub-Antarctic Kerguelen Islands where he meets Captain Len Guy of the Halbrane whose brother has vanished in the vast southern seas.

Jeorling persuades him that his brother might still be alive and they embark upon a rescue mission aboard the Halbrane, sailing ever more southwards to the mysterious, frigid, and increasingly perilous Antarctic. Disaster strikes when the ship collides with an iceberg and is lost, but the crew survive…for now. We won’t spoil the rest of the book, but it’s well worth a read, providing a fascinating glimpse into the global excitement around polar exploration at the time—it could even be considered a precursor to the Heroic Age of exploration that followed.

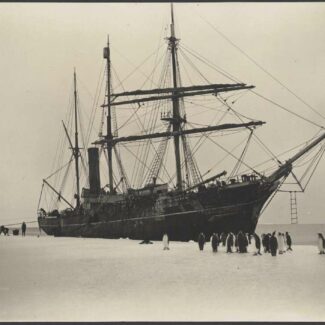

3. The Antarctic

The hard-working Antarctic was built in 1871 in Norway as a barque (it was later installed with a steam engine) and first came to the Southern Ocean as a whaling vessel. It then began a career as a wide-ranging expedition vessel. Its final voyage was as part of the 1901-1904 Swedish Antarctic Expedition led by Otto Nordenskjöld.

For this scientific expedition, the Antarctic was captained by C.A. Larsen, a Norwegian whaler who’d co-founded the Grytviken whaling station on South Georgia. As part of the expedition, Nordenskjöld and his party overwintered on Snow Hill Island along the Antarctic Peninsula, and in the austral summer of 1902-1903, the Antarctic headed for Snow Hill to pick them up. It became trapped by pack ice off the northeastern coast of the peninsula, then crushed and sunk: the first known example of a shipwreck resulting from ice entrapment and pulverization.

Remarkably, Larsen and the rest of the Antarctic crew all survived: They trekked over the ice to Paulet Island, where they spent a fierce winter sheltering in stone huts and living off seals and penguins. They were rescued in November 1903 by an Argentine ship, the Uruguay (which still exists as a museum ship anchored in Buenos Aires).

4. The Fridtjof Nansen

Built in 1885 in Newcastle-on-Tyne, England as the Garrick, a 2,563-ton cargo ship, she was sold in 1906 to the Sandefjord Hvalfangerselskab, converted to a floating factory ship and renamed Fridtjof Nansen, after the world renowned Arctic explorer who reached fame when his Fram expedition of 1893–1896 reached a record northern latitude of 86°14′.

The factory ship foundered off the Barff Peninsula on a voyage from Sandefjord to Jason Harbour, South Georgia on 10th November 1906 after hitting an uncharted reef. It sank within seven minutes, breaking into three. Nine of 58 crew sadly drowned, the remainder rescued by her accompanying whale catchers. The reef has been subsequently named “the Nansen banks” in her honor.

5. The Dundonald

Among the early recorded Antarctic shipwrecks, the Dundonald was a four-masted sailing ship built in Belfast in 1891. In March of 1907, it foundered on the rocks of Disappointment Island in the Sub-Antarctic Auckland Islands during a storm. Only 17 of the 28 crew members escaped the barque alive to come ashore on the island, and two subsequently perished.

The survivors eked out an existence on barren Disappointment Island for months, eating the albatrosses known as mollymawks and eventually crafting makeshift boats to reach a supply depot on Auckland Island. Roughly seven months later, the castaways were rescued by the Hinemoa, which had come to Auckland Island’s Port Ross to re-up the depot and noticed the half-mast flag the shipwrecked men had lowered as a signal.

6. The Endurance

There’s no more famous Antarctic shipwreck than the Endurance, the barque that served Ernest Shackleton’s Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition launched in 1914. We’ve got a whole dedicated article to that saga, but here are the basic details on the vessel itself:

In early January of 1915, the Endurance became bogged down in Weddell Sea ice, and the crew abandoned ship—only to watch it, across months, become slowly, inexorably crushed. In November of that year, having drifted with the ice more than 550 miles, the squeezed and jolted ship finally went under. Its final resting place was only discovered, nearly 10,000 feet below the Weddell’s ice-choked surface, in 2022. Thanks to the particular conditions of the Antarctic Southern Ocean, the sunken vessel, so long sought-after, is well preserved to an almost unbelievable extent.

The discovery of the Endurance—achieved by underwater drones operated by the Endurance22 expedition—ranks among the greatest shipwreck finds ever, no question.

7. The Governoren

In one of those random twists of fate the universe seems to specialize in, the Norwegian ship Governoren ended up wrecked in the Antarctic within days of the better-known debacle that doomed Endurance amid the pack ice of the Weddell Sea. The Governoren was a factory ship: a “floating factory” for the whaling industry, specially designed to haul in and process huge whales on the water, without need of an onshore facility.

In January 1915, the Governoren crew was on board enjoying a party to celebrate the end of a successful whaling season. During the revelry, a lamp was knocked over and started a fire. We’re talking a factory ship loaded with gallon upon gallon of (flammable) whale oil. The captain and crew managed to ground the burning ship and escape, but needless to say the Governoren’s whaling days were over.

You can still see the rusted, burned-out hulk of the Governoren in Foyn Harbor on Enterprise Island, which lies off the western coast of the Antarctic Peninsula and is commonly visited on cruises.

8. MV Explorer

A lot of history went down with the ship (literally) on November 23, 2007, when the MV Explorer sank in the Bransfield Strait separating the South Shetlands and the Antarctic Peninsula. This was the first cruise ship to sink in the Antarctic, for one thing—though, and let’s get this out of the way first, all passengers and crew were rescued.

What’s more, this vessel that listed awhile, then submerged en route to a chilly undersea grave, also happened to be the first ever purpose-built for Antarctic sightseeing. The roughly 240-foot-long, ice-reinforced ship first launched in 1969 as the MV Lindblad, operated by Lindblad Travel, which had inaugurated modern Antarctic tourism only three years before. While it changed hands (and names) a number of times, the rechristened Lindblad was still going strong as an Antarctic tour vessel when it met its watery fate nearly 40 years later.

The sinking of the MV Explorer remains rather mystery-shrouded, given the improbability of such a ship, a Class 1A vessel designed to withstand reasonable contact with sea ice, going down in the 21st century. The cruise ship collided with something or other at about midnight local time, and then—as the crew sought to contain the problem—it drifted into a big iceberg and sustained further damage to the same, starboard side.

An investigation into the incident concluded that human error—namely, mistaking hard land ice for more yielding first-year ice—was likely to blame, though it also commended the Explorer’s captain and crew for evacuating passengers.

9. MY Ady Gill

Among the more unique vessels in the Southern Ocean’s Antarctic graveyard is the Ady Gill, which met its end in a high-seas skirmish. This sleek fiberglass trimaran, boasting a decidedly futuristic look, was built in 2005 as Earthrace to attempt a new world record for powered circumnavigation of the globe.

After achieving that feat in 2008, Earthrace was repainted Batman-esque black and joined the environmental organization Sea Shepherd’s Waltzing Matilda campaign against Japanese whaling operations in the Southern Ocean. The Southern Ocean is a designated whale sanctuary, but at the time (2009-2010), Japan made an annual harvest of minke whales there under the auspices of legal “scientific,” as opposed to commercial, whaling. (Japan phased out its Antarctic whaling completely in 2018. You can read up on the history of whaling in Antarctica here.)

At the start of 2010, the Ady Gill and other Sea Shepherd boats were squaring off against a Japanese whaling fleet in Antarctic waters. On January 6th, after its crew had been lobbing stinkbombs onto the whaling fleet’s mothership, the Ady Gill was rammed—Sea Shepherd said intentionally, the whalers claimed accidentally—by one of the fleet’s security vessels, the Shonan Maru 2. A large chunk of the Ady Gill’s bow broke off in the collision, and all crew members—one of whom sustained minor injuries—were rescued.

Two days later, as another Sea Shepherd vessel was towing the stricken trimaran toward the French Antarctic research base of Dumont d’Urville Station, the towrope snapped, and the Ady Gill sank under the Southern Ocean, some 180 miles north of Commonwealth Bay.

10. Mar Sem Fim: The Antarctica Ghost Ship

In April 2012, a yacht owned by Brazilian journalist João Lara Mesquita—the Mar Sem Fim, aka “Endless Sea”—was in the South Shetland Islands, its four-person crew engaged in filming a documentary about the Antarctic. Fierce winds—a defining feature of the Southern Ocean and much of the White Continent—began knocking the yacht about in Ardley Cove off King George Island and shoving it against ice. The crew issued a distress call, and the Chilean Navy ended up responding; the rescue effort was a bit harrowing, given the rough conditions, but all the crew were successfully evacuated.

The yacht was not so fortunate. Overwashed water ended up freezing and splitting its hull, and the Mar Sem Fim sank into the shallow bay, coming to rest about 30 feet or so below the surface. It remained there, a frozen yacht visible with ghostly clarity, for nearly a year before Mesquita managed to arrange a recovery effort. In early 2013, inflatable buoys were used to raise the “ghost yacht” to the surface for removal and salvage.

Preservation of Antarctic Shipwrecks

Somewhat ironically, the very sea conditions that brought the majority of these ships to their fateful end have helped preserve them in their new-found subaqueous home. The cold temperatures of the Southern Ocean, combined with the fact that the immensely powerful Antarctic Circumpolar Current appears to have prevented the infiltration of Antarctic waters by wood-eating shipworms, means many historic shipwrecks here at the bottom of the world have been kept in remarkably good condition. Ernest Shackleton’s Endurance, among history’s most famous shipwrecks, being Exhibit A.

The Safety of Modern Antarctic Travel

Lest all this talk of ice-trapped and storm-pummeled ships give you the wrong idea, rest assured that modern-day travel to Antarctica is exceedingly safe, and tourists need not overly worry about rough seas, howling winds, and iceberg collisions.

Sightseeing season is well-timed for the balmiest conditions, cruise vessels are reinforced against ice and piloted by highly experienced, safety-conscious captains and crew, and today’s state-of-the-art navigational technology, safety regulations, and well-established tourist routes make for (relatively) smooth sailing.

Do shipwrecks still happen in Antarctica? Well, sure, as we’ve spotlighted in the latter examples above. But these days most moderns wrecks are fishing vessels which are more exposed to the worst of Southern Ocean seas and less specialized for withstanding icy waters.

That’s not to say you might not encounter an Antarctic shipwreck or two on your travels though—depending on your sightseeing route, you may well get to eyeball one of Antarctica’s historic wrecks!

Disclaimer

Our travel guides are for informational purposes only. While we aim to provide accurate and up-to-date information, Antarctica Cruises makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information in our guides or found by following any link on this site.

Antarctica Cruises cannot and will not accept responsibility for any omissions or inaccuracies, or for any consequences arising therefrom, including any losses, injuries, or damages resulting from the display or use of this information.