Antarctica's Sunrise, Sunset & The Green Flash Phenomenon

It’s a given that the Sun exerts a profound influence all around the globe. In the great polar ice-scape of Antarctica, our home star seems all the more precious—especially way down in the depths of the White Continent, literally at the bottom of the world, when the Sun disappears from the scene for weeks to months at a time. On the flipside, it also reigns around the clock in the sky for a goodly portion of the year.

We’ve got a whole article about the amazing solar cycle in Antarctica, that whole Midnight Sun vs. Polar Night dichotomy. In this companion piece, we’ll be digging into the liminal periods of sunrise and sunset—which, depending on where you are in Antarctica, may be daily (thereabouts) or semiannual phenomena—and a rarely seen but spectacular mirage that sometimes accompanies them to unforgettable effect.

Antarctic Sunrises & Sunsets

You might imagine that a land famous for its Midnight Sun and Polar Night doesn’t experience much in the way of sunrises and sunsets. Actually, Antarctica—particular locations and particular seasons thereof, at least—serves up some utterly spectacular sunups and sundowns, enhanced by unpolluted skies, otherworldly scenery of mountains and icebergs, and a generally vast and wide open character.

To understand sunrise and sunset in Antarctica, it helps to have a basic foundational knowledge of the White Continent’s geography, especially with regard to that important dividing line known as the Antarctic Circle.

The Antarctic Circle

The Antarctic Circle describes the latitudinal girdle defining Earth’s southern polar zone, marking the northernmost zone where the Sun remains fully above the horizon for at least one day during the austral summer and below the horizon for at least one day during the austral winter.

Although its location varies across deep time thanks to the planet’s wobble, the Antarctic Circle roughly lies at 66°30′ S. Almost all of Antarctica lies within the Antarctic Circle, but the White Continent does extend north of the Circle in a few places: most notably the Antarctic Peninsula, the northernmost extremity of the continent, but also various small areas of the East Antarctic coastline.

Along the Antarctic Circle itself, the Sun spends about 24 hours above and below the horizon on the summer and winter solstices, respectively. The duration of the “Midnight Sun” and the “Polar Night” increases the farther south one proceeds below the Circle, maxing out at about six months each at the South Pole. So the annual tally of sunrises and sunsets diminishes accordingly between the Antarctic Circle and the South Pole.

South Pole Sunrise/Sunset

At the South Pole, there’s basically a single sunrise and a single sunset over the course of a year. The Sun rises at the September equinox and then stays above the horizon (as the Midnight Sun) until it sets six months later on the March equinox, after which a half-year of Polar Night commences.

Extended transitional periods of twilight—the dim, but not full dark, experienced when the Sun is less than 18 degrees below the horizon—lead up to the September equinox and follow the March equinox, on the front and tail ends of the Midnight Sun.

As you can read more about in our article on day length in Antarctica, atmospheric refraction—the bending of sunlight as viewed from Earth—means that the Sun can be seen while it’s still technically below the horizon a day or two ahead of the September equinox and a day or two after the March equinox, which means the Midnight Sun season is a smidgen longer than the Polar Night season at the South Pole. (For the same reason—refraction—points a short ways north of the Antarctic Circle proper can experience the Midnight Sun on the summer solstice.)

Antarctica Sunrise & Sunset Mirages

Because temperature inversions are commonplace in Antarctica, with warm air overlying ice-chilled air just above the ground (or the ice pack), mirages are often seen around the horizon. Sunrise and sunset mirages are frequently seen, with striking distortions of various kinds enhancing or extending the daybreak and sundown spectacle.

The Green Flash at Sunset (or Sunrise)

Speaking of mirages: Among the most famous and elusive optical phenomena that can be observed in Antarctica’s pristine skies is the rarely observed and much-coveted green flash. The green flash describes a generally very fleeting smudge, disc, or rim of emerald—or, sometimes, blue—flaring out above the Sun when it’s nearly or entirely below the horizon.

Clear, clean, still air and a very level horizon provide the best conditions for observing the green flash. The White Continent’s icy seascapes and high, flat (and little-visited) Polar Plateau offer a prime setup, even if the odds of spotting the green flash during any given Antarctica sunset are low.

Indeed, so uncommon and unpredictable is the green flash that over the centuries it’s sometimes been passed off as a mariner’s myth. Yet photographs exist that prove its existence, and some Antarctic tourists have indeed lucked out with a once-in-a-lifetime glimpse.

The 1929 Green Flash Observation at Little America in Antarctica

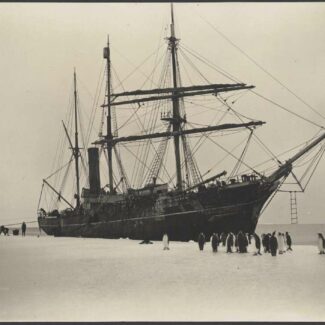

On October 16, 1929, members of Admiral Richard Byrd’s first Antarctic expedition enjoyed one heck of a green-flash spectacle—perhaps the most impressive ever recorded by human observers—from the Little America base on the Ross Ice Shelf.

They saw the green flash on and off for more than a half-hour, much longer than the usual momentary, don’t-blink-or-you’ll-miss-it firing. An academic analysis in 2015 suggested that a combination of factors likely accounted for this extended show. These included “strong atmospheric refraction” facilitating a so-called Novaya Zemyla-style mirage—which can produce a distorted image of the Sun when it’s actually several degrees below the horizon—as well as the expedition members effectively landing themselves two sunsets by climbing up Little America’s radio towers during the event.

Enjoying Antarctica Sunsets, Sunrises, and (Maybe!) the Green Flash

The majority of visitors to Antarctica travel along the coastline—especially that of the gorgeous Antarctic Peninsula, and some farther afield to, for example, the Weddell or Ross seas. This tourism takes place during the austral summer, the sightseeing enhanced by the extremely long days. Cruises to the Antarctic Peninsula in particular—which, again, is the northernmost portion of the White Continent, and which partly lies north of the Antarctic Circle—will give you daily chances to enjoy sunrises and sunsets.

And any sunrise or sunset, remember, comes with the possibility—fairly remote though it may be—of spotting the green flash…

Disclaimer

Our travel guides are for informational purposes only. While we aim to provide accurate and up-to-date information, Antarctica Cruises makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information in our guides or found by following any link on this site.

Antarctica Cruises cannot and will not accept responsibility for any omissions or inaccuracies, or for any consequences arising therefrom, including any losses, injuries, or damages resulting from the display or use of this information.