Antarctica's Whaling History & Abandoned Whaling Stations

The chance to see great whales such as blues, fins, sperm whales, and humpbacks—not to mention the smaller minke whale, orcas, and dolphins—is a major draw for travelers to Antarctica. However, it wasn’t so long ago that these majestic creatures were the draw for less nature-loving seafarers.

Here we delve into a dark side of human history and the murky-red waters of whaling in Antarctica, exploring the emergence, effect, and legacy of the commercial whaling industry on the White Continent, its Sub-Antarctic islands, and the Southern Ocean more widely.

Antarctic Whaling

Later to initiate than sealing, whaling in Antarctica became very big business indeed by the turn of the 20th century. “In terms of economic or commercial importance,” one authority has written, “whaling was by far the most important industry ever to have taken place in the Antarctic region.”

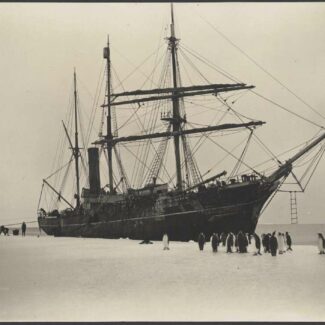

Declines in heavily hunted whale stocks in the North Atlantic and North Sea were what drew whalers south—way south—into the Southern Ocean by the early 1890s, with the first exploratory whaling expedition to Antarctica sailing from Dundee in 1892, soon followed in the same season by a Norwegian expedition led by Carl Anton Larsen.

British and Norwegian companies subsequently fast became the bigwigs of this industry, which really began in earnest with the 1904 construction of a whaling station on South Georgia by Larsen: Grytviken.

Not long thereafter, whalers were also active in the South Shetlands and South Orkneys and along the Antarctic Peninsula. The era of Antarctic commercial whaling—which, besides Great Britain and Norway, also involved numerous other nations, from Argentina to Russia—continued into the 1970s (though, as we’ll explain, a smaller-scale version persisted into the 21st century).

By the time commercial whaling arrived in Antarctica at roughly the turn of the 20th century, whalers had become significantly more efficient thanks to technological innovations such as the exploding harpoon (invented in 1868). And further advances would significantly expand the capabilities of whaling operations within just a couple of decades.

It thus so happened that whaling kicked off in Antarctica right around when it was becoming as lethally effective as it had ever been. The opening of the first whaling station on South Georgia coincided with “a time that marked the start of the most devastating of all whaling periods,” as a 2019 paper on Antarctic humpbacks put it. The end result was drastic collapses in the populations of most Southern Ocean whales.

Whale Products

What was all the massacre about? Whales were harvested for a wide variety of goods. Chief among them were whale oil produced from blubber and used for lamp-burning, lubrication, and multiple other purposes and baleen, erroneously called “whalebone,” the keratin plates that baleen whales employ in filter-feeding, which was used to make baskets, buggy whips, umbrella ribs, and other items.

Sperm whales, the only toothed whale ranked among the supersized “great whales,” were prized for sperm oil, sold at a higher price than standard whale oil, and spermaceti wax, favored for candle-burning, as well as the strange substance ambergris, produced within the whales’ intestinal tract and coveted in perfumery.

Secondary whale products included whalemeat and bone, ground up for fertilizer.

Targeted Cetaceans

The enormous summer blooms of krill, copepods, and other zooplankton in the Southern Ocean around Antarctica, powered by the seasonal phytoplankton richness of these waters, in turn draws baleen whales. The biggest of all animals (ever!), the blue whale, reaches its greatest size in the Antarctic, and became a top quarry of whalers. The blues’ great speed, and that of close and similarly streamlined cousins such as fin (or finback) and sei whales, kept these rorquals safe from the early, slow-moving 19th-century whaleboats, which preyed heavily on more sluggish baleen species such as humpback and right whales.

But by the time whaling came to the Antarctic in a major way, the availability of swifter, steam- and diesel-powered vessels and the lethal exploding harpoon—plus the ability to pump air into harpooned whales so the carcasses wouldn’t sink—meant the big, speedy rorquals were very much on the “most wanted list” of whalers.

That said, humpbacks were the first species to be intensively hunted in the Antarctic, given the relative ease with which they could be overtaken and the fact that they congregated more abundantly in nearshore waters.

The sperm whale was another prized catch, on account of those species-specific products we mentioned earlier. Mature bulls of this mighty toothed whales make annual journeys to the Antarctic in the austral summer to hunt squid and toothfish. The largest yearly numbers of sperm whales hauled in at South Georgia and South Shetland whaling stations came during December and March, reflecting the to-and-from Antarctic migration those bull sperm whales undertake.

Along with sperm whales, the biggest baleen whales were most sought-after because of the quantity of oil that could be gleaned from their carcasses. The poorly regulated and then essentially unregulated nature of Antarctic whaling—and the continued advancement of whaleship technology—made overhunting a swift, inevitable result.

So a general trend saw Antarctic whalers shifting from species to species in order of desirability as populations successively crashed, with the huge blues and then the nearly-as-huge fins exploited earlier, subsequently the smaller sei whales, and finally the comparatively small minke whale—the littlest of all rorquals—pursued by the second half of the 20th century.

Antarctica’s Shore-Based Whaling Stations

In the early days of commercial Antarctic whaling, whaleships had to haul in caught whales ashore so they could be processed: stripped of their blubber (flensed) and otherwise cut up and ground up. Therefore shore stations, which could support the necessary slipways, winches, high-pressure cookers, freshwater supplies, and other whale-processing essentials, were initially integral to the industry.

The aforementioned installation at Grytviken, along Cauldron Bay on the Sub-Antarctic island of South Georgia, in 1904 was the first shore station in the region. By 1920, about the peak of shore-based whaling in the Antarctic, there were seven stations on South Georgia as well as a single station in the Sub-Antarctic Kerguelen Island and one each in the Antarctic South Shetland and South Orkney islands.

The South Shetland and South Orkney shore stations were thus the only of their kind in Antarctica proper. The South Shetland site was the Norwegian Hektor Whaling Station (also known as New Sandefjord), built in 1912 within the flooded caldera of Deception Island, on the doorstep of the aptly named Whaler’s Bay. In the South Orkneys, a Norwegian shore station was built in 1921 along Factory Cove on Signy Island.

Antarctic Whaling Factory Ships & Pelagic Operations

Antarctic whaling transformed dramatically in the mid-1920s. The reason? The innovation of factory ships, which could process whales offshore without land-based support. These floating factories were aided by catcher boats (aka whalecatchers), which could speed about harpooning whales and leaving the floating carcasses for factory ships to attend to.

In 1923, C.A. Larsen, the Norwegian whaler who’d helped found the Grytviken whaling station in 1904, led a factory ship and a catcher fleet into the Ross Sea: the real launch of this new, deadlier-yet era of Antarctic whaling. At first, factory ships still had to anchor in sheltered harbors where calm conditions and a freshwater supply allowed them to process killed whales. Such mooring refuges ranged from Factory Cove in the South Orkneys and Admiralty Harbour in the South Shetlands to Paradise Harbour and Port Lockroy along the Antarctic Peninsula

But by 1925, the use of onboard slipways and evaporators (for making freshwater) allowed factory ships to haul carcasses aboard to be flensed, the blubber melted into oil, and the cut-up meat and pulverized bone packed into barrels.

In other words, these floating factories became essentially fully independent from coastal hubs (though the aforementioned harbors were still utilized), and vast reaches of the Southern Ocean were opened up to whaling. And given those pelagic waters fell outside national jurisdictions, the industry could essentially run rampant, and soon Japanese and German factory ships challenged what had been a prevailing British and Norwegian hegemony.

Shore stations declined and mostly closed with the advent of factory ships and pelagic whaling—during the 1930/31 season a single whaling ship (Kosmos) alone produced more whale oil than all of South Georgia’s remaining shore stations combined; the economic upheaval of the 1930s, which saw whale-oil prices plummet, also contributed.

A few of the stations on South Georgia, however—Grytviken, Husvik, and Leith Harbour—continued to be used into the 1960s. Shore-based operations there not only included whale-processing, but also servicing pelagic whaleships.

Impacts of Antarctic Whaling

As with fur seals before them, Antarctic whales suffered huge—and rapid—population declines in the face of this free-for-all-style exploitation. Close to 25,000 humpback whales were killed in a little more than a decade, between 1904 and 1916, off South Georgia. (Indeed, at their closing, in just six decades of operation, South Georgia whaling stations had processed an astonishing 175,250 cetaceans.) Worldwide, a single whaling season, 1930-1931, saw better than 29,000 blue whales harvested, much of that going down in the Antarctic region.

Whaling pressure in the Antarctic became even greater after World War II. “More than half of all whales officially harvested in Antarctica were hunted in the years following the Second World War,” Lyndsie Bourgon wrote in a Aeon feature on the industry. The 1961-1962 Antarctic whaling season saw more than 66,000 whales killed. North of 5,000 sei whales annually—and sometimes many more than that—were taken in the Southern Hemisphere from 1960 to 1972.

It’s estimated that during the 20th century, industrial whaling operations harvested more than 725,000 fin whales, 400,000 sperm whales, 360,000 blue whales, and 200,000 each of sei and humpback whales. Blue whales in the Southern Ocean, among the most prized species, are thought to have endured a 97% decline over this period.

Protecting Antarctic Whales

By the 1920s, international concern was mounting over the sustainability of commercial whaling. In 1930, the Bureau of International Whaling Statistics was established to monitor the industry, and the following year 22 nations—but not several of the major whaling ones—signed the Convention for the Regulation of Whaling.

In 1948, the International Whaling Commission (IWC) was created as the decision-making body of a new International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling. Blue whales received international protection in 1965, and by the late 1970s the IWC had also banned commercial whaling of fin and sei whales in the Southern Ocean.

The IWC implemented a moratorium on all commercial whaling beginning in the 1985-1986 season. The moratorium remains in effect, though Norway and Iceland filed objections to it and continued to engage in commercial harvest of minke (and, in the case of Iceland, also North Atlantic fin whales).

Meanwhile, Japan kept harvesting whales in Antarctica from 1986 to 2018 under a “scientific whaling” permit: a very controversial practice that ended when, in 2019, Japan left the IWC and, no longer subject to the moratorium, resumed commercial whaling in its territorial waters.

Thus, Antarctic waters no longer experience any legal commercial or “scientific” whaling. The Southern Ocean has been a designated whale sanctuary since 1994 (though, as detailed above, Japan conducted whaling within it until 2018).

The Abandoned Whaling Stations of Antarctica

Serving as a valuable and poignant reminder to visitors, the vestiges of the whaling era in Antarctica staunchly remain visible in many places, their haunting ruins and dark history belligerently refraining from being whitewashed by the harsh Antarctic elements.

Though volcanic eruptions have erased some of the abandoned Hektor Whaling Station on Deception Island in the South Shetlands, cruise passengers exploring the shores of Whalers Bay can still see relics such as blubber-processing digesters, remnants of whaleboats, and scattered bones from those bygone days.

Fewer itineraries take in farflung Signy Island in the South Orkneys, but tourists are occasionally able to visit the British Antarctic Survey Base there, occupying the site of the historical Norwegian whaling station on Factory Cove.

South Georgia boasted the largest concentration of shore whaling stations in Antarctica, with no fewer than seven in operation at one point or other, including:

- Grytviken

- Husvik

- Ocean Harbour

- Leith

- Stromness

- Prince Olav

- Godthul (factory ship support only)

Modern-day visitors to this stunningly beautiful Sub-Antarctic island can see the ruins of most of these stations, but public entry to the majority is prohibited for safety concerns over deteriorated structures at risk of collapse and potential exposure to airborne asbestos fibres and hazardous heavy oils. Grytviken, the original and best example of all the whaling stations, is however, very much visitable.

Grytviken Whaling Station

Located at the west end of King Edward Cove in Cumberland Bay, Grytviken Whaling Station is an incredibly important site in Antarctic history. Not only was it the first shore-based whaling station constructed in the modern era (built in 1904), but it was also the longest operating of the whaling stations on South Georgia (closing in 1965).

The station will forever be associated with its Norwegian founder, Carl Anton Larsen, the pioneer of modern Antarctic whaling, as well as being both the last port of call for the Endurance on its fateful 1914 voyage and the final resting place of Sir Ernest Shackleton, the famous Antarctic explorer who is buried in the cemetery at Grytviken. Others may know it as the site of the largest whale ever recorded, a 33.58m (110ft 17in) blue whale that was processed at the site in 1912.

While many buildings and structures were lost during asbestos clearance works in the early 2000s, important elements of the layout remain, including the factory bases and plant, jetties, beached vessels, and accommodation structures. Its landmarks also include the 1913-built Whaler’s Church, Ernest Shackleton’s grave, and the South Georgia Museum, housed in the onetime station manager’s home and full of information on the whaling era.

Whaling Shipwrecks in Antarctica

As whale numbers declined and whaling bans came into force, whaling fleets in the Southern Ocean became obsolete, and often proved unviable to relocate. Many were deliberately sunk, with others simply left at docksides. As such, visitors to South Georgia have ample opportunity to witness the rusting remnants of some of the most elderly whaling ships, now sanctuary for seabirds and other creatures as nature reclaims them.

At Grytviken beach, you can’t miss the shipwrecks of the two small whalecatchers-turned-sealers Petrel (built 1928) and Albatross (1921), as well as the sealer Dias (1906). Elsewhere you may witness the larger whalecatcher Karrakatta (built 1912) stored on a slipway at Husvik, and, if you’re lucky, at lower water you may catch a glimpse of Fortuna (built 1904), part of Larsen’s first whale catcher fleet, just north of Hope Point.

Other wrecks of various industry-related vessels involved in the construction and operation of South Georgia’s whaling stations can also be found around the island, the most notable being the aptly named coal hulk Brutus (built 1883), lying partly submerged just outside the inner cove of Prince Olaf Harbour.

Governoren

Further south on the Antarctic Peninsula, between Nansen Island and Enterprise Island in Wilhelmina Bay, lies the wreckage of the legendary Norwegian whaling factory ship, Governoren or Guvernøren (built 1891). One of the largest whaling factory ships of her time, she was capable of collecting 22,000 gallons of whale oil per season.

On January 27th 1915 at the annual end of season party, an overly zealous reveler accidentally knocked over an oil lamp setting fire to the ship. In an attempt to save the vessel and its crew (and the precious and highly flammable cargo), the captain deliberately ran her aground at Foyn Harbor—an anchorage incidentally named after another whaling factory ship, the Svend Foyn—and thankfully the entire crew of 85 were able to escape. The ship, however, was lost and now lies in wait for the occasional Antarctic cruise visitor, proving especially popular among any scuba diving passengers with sufficient cold-water experience.

Whale-watching in Antarctica Today

Whale stocks in Antarctic waters are still in recovery mode after those many decades of intense whaling. That’s a reminder of how devastating humanity’s impact can be on other forms of life—not least those largest and slowest-reproducing among them.

Yet the recovery of whales in the Southern Ocean is on the right track, and the rebound of some species—humpbacks, maybe most notably, but also southern right whales—has been truly heartening. Some spectacular aggregations of fin whales, second-biggest of all whales (and all living creatures), have lately been documented off the Antarctic Peninsula, including multiple feeding groups better than 100 strong.

This is all wonderful not only for nature enthusiasts keen for a glimpse of pluming spouts and high-raised flukes, but also for the ecological implications: There’s increasing evidence that Antarctica’s great whales, through their feeding (and, ahem, fecal) activities, play a fundamental role in nutrient cycling in the Southern Ocean: the concept of the so-called “whale pump.”

With the trajectory for Antarctica’s previously hammered whales on the right side of the curve, and opportunities to spot these magnificent leviathans—from spritely minkes to acrobatic humpbacks and even the occasional supersized blue, sometimes spotted, for example, on Drake Passage crossings—get richer and richer. And that’s not even counting the sleek, swift orcas that ply Antarctic waters in multiple forms (ecotypes, subspecies, or maybe even species—biologists aren’t settled on the issue).

Learn more about Antarctica’s whale lineup—and the White Continent’s whale-watching opportunities—right here.

Disclaimer

Our travel guides are for informational purposes only. While we aim to provide accurate and up-to-date information, Antarctica Cruises makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information in our guides or found by following any link on this site.

Antarctica Cruises cannot and will not accept responsibility for any omissions or inaccuracies, or for any consequences arising therefrom, including any losses, injuries, or damages resulting from the display or use of this information.