Antarctica's Bay of Whales & Its Place In History

First explored in 1842 by Sir James Clark Ross, the Bay of Whales represents—or represented, depending on whether or not you think it still exists—one of the great geographic and historical landmarks of Antarctica.

Situated in that near-pristine sea named for Ross, this natural harbor along the Ross Ice Shelf played a significant role in the exploration of the White Continent, most famously marking the jumping-off point for Roald Amundsen’s successful journey to the South Pole, among the great feats in the history of world exploration.

Introducing the Bay of Whales

The Bay of Whales historically existed (since at least the beginning of the last century) as an alcove along the front of the Ross Ice Shelf, that greatest of all ice shelves that covers the southern reach of the 370,000-square-mile (960,000-square-kilometer) Ross Sea.

The bay—an ice harbor or iceport—was situated to the north of the ice rise called Roosevelt Island and to the west of the Edward VII Peninsula’s Cape Colbeck. Have a look at a Bay of Whales, Antarctica map below:

The location of Antarctica’s Bay of Whales on the Ross Ice Shelf, just north of Roosevelt Island

Given it was outlined by shifting, unstable ice, the size and shape of the Bay of Whales weren’t constant. According to the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research, surveys during the second of Robert E. Byrd’s Antarctic Expeditions in 1934 suggested the iceport may have marked “the junction of two separate ice systems” within the Ross Ice Shelf, and recognized that the ridge of Roosevelt Island (the ice rise identified and named on this expedition) influenced movements of these ice systems and thus likely the maintenance of the bay.

When exposed in summer, the Bay of Whales represented the southernmost open water of the Ross Sea—indeed, of the entire World Ocean—and the closest a ship could advance toward the South Pole. A strategic spot, to say the least!

Origin of the Name “Bay of Whales”

Though it had been sighted decades before, the Bay of Whales earned its name in 1908 from none other than Sir Ernest Shackleton, among the truly legendary Antarctic explorers of all time. (Well, let’s be real: Given his almost unbelievable leadership during the Imperial Transantarctic Expedition of the following decade—the ice-trapped Endurance, the perilous lifeboat journey aboard the James Caird, the crossing of South Georgia, etc.—we can probably just pronounce him one of the truly legendary explorers of all time, no geographic qualifier necessary.)

Leading Southern Ocean marine researcher David Ainley believes Shackleton’s moniker stemmed from observations of orcas, or killer whales—and, specifically, what today’s marine biologists term Ross Sea or Type C orcas, the smallest of the multiple Antarctic killer-whale types. Recalling his foray into the iceport aboard the Nimrod, Shackleton wrote:

All around us were numbers of great whales showing their dorsal fins as they occasionally sounded […] We named this place the Bay of Whales, for it was a veritable playground for these monsters.

Writing a few years later, in 1912, equally enshrined Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen noted that orcas showed up in the Bay of Whales around the time its fast ice (sea ice that’s attached to bedrock, ice shelves, or grounded icebergs) was receding: “The name of the Bay of Whales […] is appropriate enough; for from the time of the break-up of the sea-ice this huge inlet in the Barrier [the name early Antarctic explorers applied to the Ross Ice Shelf] forms a favorite playground for whales, of which we often saw schools of as many as fifty disporting themselves for hours together.”

These early observations jibe with modern-day research suggesting killer whales key into breaking-up fast ice to munch on toothfish, more likely to congregate near the sea surface—and thus become more accessible to an orca—under ice than in ice-free waters. And the numbers Shackleton and Amundsen reference are also in line with the habits of Type C orcas, which often gather together 50- to 100-whales strong.

Historical Importance of the Bay of Whales, Antarctica

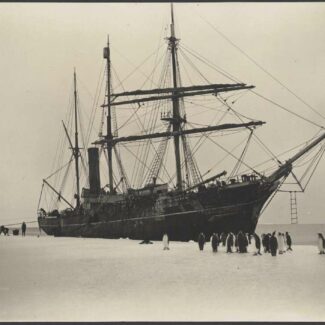

The best-known historical association of the Bay of Whales is with Amundsen’s 1910-1912 Norwegian Antarctic Expedition aboard the Fram. That quest for the South Pole famously competed against the British Antarctic Expedition of the Terra Nova, helmed by Sir Robert Falcon Scott.

Scott chose Ross Island in the Ross Sea’s McMurdo Sound as the launchpad for his attempt on the South Pole. He’d used the island as a base of operations on a previous expedition, and intended to trace a route from there—one Ernest Shackleton had pioneered in 1908—across the Ross Ice Shelf and up onto the Antarctic Polar Plateau.

Amundsen, by contrast, selected the Bay of Whales as his starting point: one that was about 60 miles closer to the Pole than Scott’s. That nearer proximity—plus a whole host of other, much-debated factors, not least the Amundsen party’s use of and prior experience with sled dogs and skis—likely helped the Norwegian team become the first people to ever set foot at the South Pole on December 14, 1911.

Historic map sketches of the Bay of Whales with annotations taken from the US Geological Survey’s field notebook collection

Amundsen and his men safely returned to their base camp Framheim (portrayed in the painting by Andreas Bloch above) at the Bay of Whales the following month. Scott’s South Pole party also reached their goal, but about a month behind Amundsen, and all five of its men perished on the return march.

The auspicious location of the Bay of Whales saw it serve as the base for a number of later Antarctic expeditions, including multiple versions of the “Little America” camps established on the Ice Shelf by Richard Byrd.

The Bay of Whales was also used as a harbor by factory ships during Antarctica’s industrial-whaling days, with fleeter catcher ships towing in baleen whales killed out on the Ross Sea’s continental slope some distance away.

Does the Bay of Whales Still Exist?

Whether the Bay of Whales exists today is somewhat debatable. “Officially” speaking, it was obliterated in October of 1987 by the calving of the huge Iceberg B-9 off the Ross Ice Shelf between the Bay of Whales and Okuma Bay edging Cape Colbeck. A 1990 report on that calving event noted that a “new indentation” in the Ross Ice Shelf created when Iceberg B-9 (which initially measured some 154 by 35 kilometers) broke off may have represented the earliest reformation of the natural ice harbor, and that, long-term, “the continued existence of the Bay of Whales may depend upon a mean ice front location within several tens of km north of Roosevelt Island.”

While the Bay of Whales is often spoken of as a former geographic feature, the continued effect of Roosevelt Island in slowing and warping movement of the Ross Ice Shelf may continue to create an embayment—albeit one prone to reshaping and periodic disappearance—in the ice rise’s lee. And some expedition and cruise ships in the Ross Sea continue to visit the history-washed site of the Bay of Whales, even though its position shifts with time.

Disclaimer

Our travel guides are for informational purposes only. While we aim to provide accurate and up-to-date information, Antarctica Cruises makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information in our guides or found by following any link on this site.

Antarctica Cruises cannot and will not accept responsibility for any omissions or inaccuracies, or for any consequences arising therefrom, including any losses, injuries, or damages resulting from the display or use of this information.