Famous Antarctic Explorers: From Shackleton To A Robot?

- 12 Famous Explorers of Antarctica (and the Antarctic Realm)

- 1. Captain James Cook

- 2. Thaddeus von Bellingshausen

- 3. James Weddell

- 4. James Clark Ross

- 5. Robert Falcon Scott

- 6. Roald Amundsen

- 7. Ernest Shackleton

- 8. Douglas Mawson

- 9. Richard Byrd

- 10. Ingrid Christensen

- 11. Ranulph Fiennes & Mike Stroud

- 12. LORAX

- Can You Explore Antarctica?

The last continent to be discovered, Antarctica has, without question, seen some of the most famous and remarkable exploits of modern exploration of anyplace on Earth. Here, science and adventure continue to overlap as researchers brave the world’s harshest elements and vastest wilderness to better understand everything from the prehistoric continent of Gondwana to modern-day climate change.

In this article, we’ve rounded up a dozen of the most famous Antarctic explorers. Keep in mind it’s far from exhaustive when it comes to reflecting important individuals in Antarctic history, and a whole slew of other candidates could be swapped in. But it’s certainly a lineup representative of the courage, hardiness, and ambitions both historical and modern Antarctic explorers have demonstrated here on the White Continent!

12 Famous Explorers of Antarctica (and the Antarctic Realm)

The following Antarctic explorers list is presented in rough chronological order, not in any kind of ranking of importance. And as you’ll see, we’re taking as our geographic area under consideration the whole Antarctic zone south of the Antarctic Convergence, a critical oceanic frontier lying between 50 and 60 degrees S, thereby including one expedition leader (the first on our roster, in fact) who never technically saw the White Continent itself.

1. Captain James Cook

Among the foremost explorers in history, Captain James Cook of the British Royal Navy mapped vast portions of the Pacific as well as the Southern Ocean on three mind-bogglingly ambitious voyages between 1768 and 1779. The second of these journeys, conducted from 1772 to 1775, saw Cook and his ships (the Resolution and Adventure) become the first to cross the Antarctic Circle, a line of latitude reckoned at about 66 degrees S. This also saw Cook’s expedition attaining the southernmost position people had definitively visited up until that point: 71 degrees 10’ S on February 3, 1774, when further poleward progress was halted by pack ice.

Besides its exploits south of the Antarctic Circle, that second voyage of Cook’s notched the first landing on South Georgia and the discovery of the South Sandwich Islands (both popular subpolar destinations on modern-day cruises to Antarctica).

2. Thaddeus von Bellingshausen

The Russian admiral Fabian Gottlieb Thaddeus von Bellingshausen is credited with being the first person to actually see the Antarctic continent. Leading the ships Vostok and Mirnyi—and crossing the Antarctic Circle for the first time since Cook’s voyage—he described “an ice shore of extreme height” on January 27, 1820. This was probably the Fimbul Ice Shelf of Queen Maud Land.

Bellingshausen’s expedition, which circumnavigated the Southern Ocean, also charted the first lands south of the Antarctic Circle: Peter I and Alexander islands, situated off the western coast of the Antarctic Peninsula in what became known as the Bellingshausen Sea.

3. James Weddell

British sealer James Weddell led an expedition deep into Antarctic waters via the Jane and Beaufoy from 1822 to 1824. On February 20, 1823, these ships steered farther south than any before them, attaining 74 degrees 15’ S in what we now call the Weddell Sea. He also first described one of the iconic Antarctic pinnipeds, the Weddell seal.

4. James Clark Ross

James Clark Ross of the British Royal Navy led one of the all-time Antarctic expeditions from 1839 to 1843, commanding the ships Erebus and Terror. The Ross Expedition plied hitherto-unknown waters of what came to be called the Ross Sea, viewing for the first time the white battlement of the Ross Ice Shelf and the mountain cones of Ross Island—the crowning volcanoes of which the crew named after their sturdy vessels.

Ross and his men also discovered the Transantarctic Mountains and identified new islands along the Antarctic Peninsula. (Like Weddell, Ross—in addition to a slew of geographic landmarks—has an ice seal named after him.)

5. Robert Falcon Scott

Another British Royal Navy officer, Robert Falcon Scott, is easily on the shortlist of the top two or three most famous Antarctica explorers. He’s also perhaps its foremost tragic figure.

Scott’s first journey to the White Continent was the 1901-1904 National Antarctic Expedition, which explored more of the Ross Sea and made a go at the South Pole, though that intrepid party—consisting of Ross as well as Ernest Shackleton and Edward Wilson—was forced to turn back on December 30, 1902, still some 410 miles from their goal. This expedition logged the southernmost point yet: 82 degrees 11’ S.

In 1910, Scott launched the British Antarctic Expedition aboard the Terra Nova. This endeavor also had its eyes on being the first to the South Pole, but Scott’s party was beaten to the punch by Roald Amundsen. Scott and his companions—Lawrence Oates, Henry Robertson Bowers, Edward Wilson, and Edgar Evans—reached the South Pole on January 18, 1912—a bit more than a month after Amundsen’s party—and then endured a draining slog back toward the expedition’s base at Cape Evans on Ross Island.

During that return ordeal, Evans perished on the Beardmore Glacier on February 17, 1912; Oates died a month later on the Ross Ice Shelf. Scott, Wilson, and Bowers met their end in a snowbound tent only about 11 miles shy of their final supply point of One Ton Depot.

Scott’s poignant final diary entries, written on March 29, 1912, probably account for the most famous few lines in the annals of Antarctic exploration, including, “Had we lived, I should have had a tale to tell of the hardihood, endurance, and courage of my companions which would have stirred the heart of every Englishman. These rough notes and our dead bodies must tell the tale […]” His closing sentences: “We shall stick it out to the end, but are getting weaker, or course, and the end cannot be far. It seems a pity, but I do not think I can write more.” He signed off with “For God’s sake look after our people.”

6. Roald Amundsen

Scott’s great rival in the quest for the South Pole was the Norwegian Roald Amundsen, among the most distinguished polar explorers in history. Amundsen had been a member of Adrien de Gerlache’s 1897-1899 Belgian Antarctic Expedition, which resulted in the first overwintering in Antarctica when its ship, the Belgica, became locked in sea ice off the Antarctic Peninsula in March 1898.

Amundsen and four companions from his 1910-1912 Norwegian Antarctic Expedition on the Fram—Helmer Hanssen, Olav Bjaaland, Sverre Hassel, and Oscar Wisting—became the first people to set foot at the South Pole at 3 PM on December 15, 1911. They fared better than Scott’s party close at their heels; Amundsen and his men returned safely to their base at the Bay of Whales, having covered about 1,860 miles in 99 days.

Amundsen engaged in many expeditions and adventures on the other side of the world as well, most notably a flyover of the North Pole in the airship Norge in 1926 that may or may not rank as the first visit to Earth’s northernmost point, depending on the veracity of several prior claims going back to Frederick Cook in 1908. Indeed, Cook’s announcement of reaching the North Pole and that of Robert Peary the following year convinced Amundsen, who had originally been organizing an Arctic expedition, to set his sights on the South Pole instead for his Fram odyssey.

The Arctic marked Amundsen’s grave, too: The Norwegian explorer went missing on a rescue mission on June 18, 1928, presumed to have died in a plane-wreck in the Barents Sea.

7. Ernest Shackleton

Irish-born Ernest Shackleton pulled off some of the most incredible exploits in the history of Antarctic exploration. As mentioned above, Shackleton was a member of Robert Falcon Scott’s National Antarctic Expedition and accompanied Scott and Edward Wilson on that unsuccessful 1902 trek for the South Pole; Scott and Wilson, of course, would die a decade later returning from that coveted piece of ground.

Shackleton led the British Antarctic Expedition of 1907-1909 aboard the Nimrod, the achievements of which included the first ascent of Mount Erebus (the southernmost of the world’s active volcanoes) and a new southernmost foray to 88 degrees 23’ S.

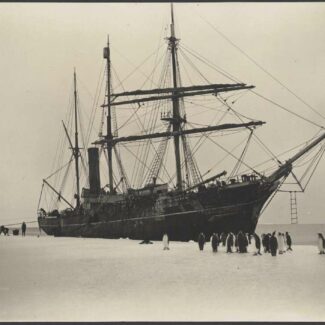

But Shackleton is best known for his 1914-1917 Imperial Transantarctic Expedition, which aimed to make the first overland crossing of the White Continent via the South Pole. That effort failed when Shackleton’s ship, the Endurance, became trapped in the pack ice of the Weddell Sea and slowly crushed over eight months, finally sinking in November 1915. Shackleton’s men endured a harrowing survival odyssey, first camping out for months on the ice, then escaping to Elephant Island via three lifeboats.

From there, Shackleton disembarked with a small crew for South Georgia nearly 900 miles away, where they managed to land a bit more than two weeks later. Shackleton and two others made the first traverse of that island’s mountainous interior to reach the whaling station of Stromness, and then engineered the rescue of his remaining Endurance crew still marooned on Elephant Island.

Shackleton aimed for a return to the White Continent on a 1921 expedition funded by the British businessman John Q. Rowett, but died of a heart attack on South Georgia on January 5, 1922. His second-in-command, Frank Wild, took over leadership of the Shackleton-Rowett Expedition, which forayed, among other places, into the Weddell Sea. You can visit Shackleton’s grave in Grytviken on South Georgia: a suitably remote and scenic final resting place for this legendary Antarctica explorer.

8. Douglas Mawson

The Australian Douglas Mawson was a geologist and explorer who’d been a part of Shackleton’s Transantarctic Expedition, and whose own arduous Antarctic survival epic roughly overlapped with the saga of the Endurance.

Mawson helmed the Australasian Antarctic Expedition of 1911-1914, which made important scientific observations in East Antarctica out of a main base at Cape Denison (which—not without justification—Mawson termed “the windiest place on Earth”). Among other newly described landmarks logged by Mawson’s expedition was the Shackleton Ice Shelf.

Mawson and two companions, Belgrave Ninnis and Xavier Mertz, forayed by sledge into unknown backcountry of George V Land as part of the expedition’s Far Eastern Party in late 1912. Several hundred miles from Cape Dennison, Ninnis was lost in a crevasse, and Mertz fell ill and died on the return trip. This left Mawson to trek alone and starving roughly 100 miles to reach the safety of Cape Dennison: a remarkable solo trial.

9. Richard Byrd

An officer of the U.S. Navy, Richard Byrd achieved some important milestones in the Antarctic as part of a rich career of military service and exploration. In a flight on the Floyd Bennett lasting more than 18 hours, Byrd and several companions—Bernt Balchen, Harold June, and Ashley McKinley—became the first to cross over the South Pole by airplane on November 29, 1929. (This came after Byrd’s 1927 flight across the Atlantic and an alleged flight in 1926 over the North Pole—a contested feat that, if true, put Byrd’s flyover mere days before Amundsen’s confirmed North Pole flight on the Norge.)

Byrd later went on to head the U.S. Navy’s Operation HIGHJUMP in 1946 and 1947, based on the Ross Ice Shelf and generating tens of thousands of valuable aerial photographs over Antarctica.

10. Ingrid Christensen

In terms of identifying the first woman to explore Antarctica, the Norwegian Ingrid Christensen is definitely among the candidates. She made several journeys to the White Continent alongside husband Lars aboard the Thorshavn during the 1930s, being credited along with Mathilde Wegger as the first women to see Antarctica in 1931.

In 1937, her fourth visit to the bottom of the world saw Christensen become the first woman to fly over Antarctica and, with a visit to the Scullin Monolith area, likely the first to set foot on the mainland itself. (Two years previously, however, the Danish-Norwegian explorer Caroline Mikkelsen had come ashore on an Antarctic island.) A portion of the East Antarctica seaboard is named for her: the Ingrid Christensen Coast.

11. Ranulph Fiennes & Mike Stroud

The British explorer Ranulph Fiennes and nutrition expert Mike Stroud made the first unsupported crossing of the Antarctic continent on foot in 1992 and 1993, covering roughly 1,600 miles. Thanks to Stroud’s expertise and interest in human physiology under extreme conditions, the energetic challenge the two men underwent was scientifically tracked.

A 2018 Outside article by Alex Hutchinson noted some of the findings: “Careful measurements of energy consumption using isotope-labeled water showed that [Stroud and Fiennes] were burning an astounding 7,000 calories a day for 96 days. During one ten-day period while they ascended the [Antarctic Polar] plateau, they averaged 11,000 calories a day. Even though they were eating 5,000 calories a day, they lost 48 and 54 pounds respectively during the trip.

12. LORAX

The superlative rigors of the Antarctic environment have led some to investigate the possibility of conducting non-human exploration amid its white wastes. An example is the Life on Ice: Robot Antarctic Explorer, or LORAX, developed by The Robotics Institute of Carnegie Mellon University. Prototyped in 2005, LORAX is a solar- and wind-powered rover designed to someday survey microbial life on the Antarctic ice sheet.

Can You Explore Antarctica?

The careful regulation of Antarctic visitation, designed to protect this most pristine of all continents, means your average tourist doesn’t have free rein to ramble its severe wilderness at will. (That’s a good thing on many levels.)

But a getaway to the White Continent—very much a possibility—is nonetheless the adventure of a lifetime, giving you the chance to see astounding polar landscapes and wildlife, and at least get a taste for a Shackletonian-type experience via skiing and snowshoeing outings, landfalls on remote penguin beaches, even campouts on the snow.

Disclaimer

Our travel guides are for informational purposes only. While we aim to provide accurate and up-to-date information, Antarctica Cruises makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information in our guides or found by following any link on this site.

Antarctica Cruises cannot and will not accept responsibility for any omissions or inaccuracies, or for any consequences arising therefrom, including any losses, injuries, or damages resulting from the display or use of this information.