A History of Fur & Elephant Seal Hunting In Antarctica

From penguin-gobbling leopard seals and bellowing “beachmaster” elephant-seal bulls, to the fuzzy pups of Ross, Weddell, and crabeater seals, the pinnipeds of the Antarctic rank among the region’s most charismatic wildlife. Whatever the species, they’re always a thrill to view on a cruise to the bottom of the world.

But you may not know that they also happen to figure prominently in Antarctic history, given the once booming market for pelts and oil derived from their fur and blubber helped spur exploration of the Southern Ocean’s deep reaches, including the islands and coasts of the White Continent itself.

Your appreciation of these flippered, bewhiskered, dewy-eyed marine mammals—and the remarkable marine ecosystems they play such important top-level roles in—can only be deepened by understanding a bit about the historical gauntlet of hunting they passed through to keep doing their thing in the briny, icy wilds of the Southern Ocean.

Seal Hunting in Antarctica

“Sealing was the earliest Antarctic industry,” Bjorn Basberg and Robert Headland wrote in a 2008 paper. “It was characterized by large fluctuations in catches and shifts in sealing grounds as seals were almost exterminated in particular locations—in an era completely lacking regulations.”

Sub-Antarctic sealing was underway within a few years of Captain Cook rediscovering and naming South Georgia and discovering the South Sandwich Islands in 1775. In fact, there’s some evidence sealers had already chanced upon the remote South Sandwich archipelago before Cook’s formal discovery.

Sealers began plundering South Georgia between 1786 and 1788, with British and then American operations out of New England exploiting the island’s abundant fur seals.

Between the late 18th and mid-19th century, the sealing industry—dominated by Britain and the U.S.—had expanded across the Southern Ocean to encompass not only South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands but also other sub-Antarctic island groups, including the Kerguelens, Heard Island, and Macquarie Island.

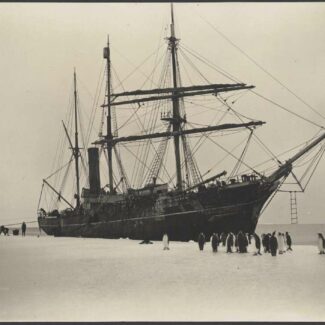

The seal trade was at its zenith in the 1821/22 season when close to 100 vessels were officially employed in Southern Ocean sealing. Relentlessly seeking new hunting grounds as Sub-Antarctic pinniped colonies were decimated, sealers forayed farther south to the Antarctic archipelagos of the South Shetlands and the South Orkneys, and then farther yet to the Antarctic Peninsula, likely becoming the first people to discover the Antarctic continent and many of its islands and bays, but rarely documenting their discoveries for fear of betraying their prized hunting ground locations.

Enjoying the sun

Fur Seal Hunting

The initial target, in the Sub-Antarctic islands, was the Antarctic fur seal, whose dense fur was coveted for hats and other clothing. Sealskins became an important part of the global fur trade, with London and Canton being major markets.

The scale of the overexploitation pursued by sealers back in the day is staggering to think about. In 1800, for example, Captain Fanning Astoria alone took some 57,000 fur seals from South Georgia. With that sort of level of harvest, it’s no surprise fur seals were nearly completely wiped out on South Georgia as early as 1820.

By 1824, just four years after American sealing captain Nathaniel Palmer named Deception Island in the South Shetlands, sealers had killed some 500,000 fur seals there, efficiently exhausting the resource.

Thus sealers pursued a roving, semi-nomadic business pillaging for fur seal pelts, devastating numbers in short order on one island or archipelago, then questing farther out for yet-untapped seal colonies. After being hammered, seal populations on some islands did recover somewhat in the following decades, only to be targeted again.

It’s reckoned that a minimum of seven million fur seals were killed in the Sub-Antarctic and Antarctic region before 1833 alone, and by the early 20th century, fur seals became so exceedingly rare throughout the region—a lone male was sighted on South Georgia in 1916—that hunting them became unprofitable and the fur seal industry came to an end.

Enjoying each other

Elephant Seal Hunting

The other big quarry during the historical period of Antarctic/Sub-Antarctic sealing was the southern elephant seal. As fur seal numbers declined, sealers shifted their attention to those huge pinnipeds—not after their hides, but their blubber, which was rendered, a la whale blubber, into high grade oil used for lighting, lubrication and leather treating.

Because the processing method and equipment for elephant-seal and whale oil were similar—and the fact it was a close substitute for whale oil and commanded a near-equal price—many whaling vessels also moonlighted in hunting elephant seals (aka “elephanting”). Indeed, as whale numbers plummeted, some whalers shifted over to elephanting, as happened with the whalecatchers Petrel and Albatross, whose beached hulls, together with that of the sealer Dias, can be seen half-submerged on South Georgia today. (Also on South Georgia’s beaches you can still see large cast iron ‘try’ pots in which the seal blubber was boiled down).

An estimated 800,000 elephant seals were plundered at the main Sub-Antarctic catching grounds of South Georgia, Kerguelen, Heard and Maquarie during the 19th century, although this number is likely to be significantly understated due to figures often being included in whale oil production. Between 1904 and 1964 the (licensed) elephanting estimates had dropped to around 260,000.

Despite southern elephant seals declining significantly during this later sealing era—elephanting was somewhat more sustainable than fur-seal hunting, and on South Georgia it even became regulated. Whereas fur sealing had effectively ceased at the turn of the 20th century, South Georgia continued elephanting, with more than 2,000 tons of seal oil harvested from South Georgia in 1955-1956, according to the Friends of South Georgia, before the closure of the island’s remaining whaling stations in the mid-1960s also brought a close to the sealing industry.

Peace of mind

The Status of Antarctic & Sub-Antarctic Seals Today

After heavy exploitation, fur seals and southern elephant seals, as well as the four other seal species found living in Antarctica, have recovered well and are all classified as ‘least concern’. Indeed, the crabeater seal of Antarctica has recovered to such an extent that it is now reckoned as perhaps the most numerous large wild mammal on the planet.

This is thanks, in no small part, to such strong conservation measures as the Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Seals, incorporated within the Antarctic Treaty System in the 1970s. This agreement protects all six of the Southern Ocean pinnipeds found south of the Antarctic Convergence from over-exploitation, with total protection given to the rare Ross seal, southern elephant seal and fur seal species, but some permissible annual catch limits for crabeater, leopard, and Weddell seals.

As a result, pinniped-peeping is, thankfully, a fruitful pursuit for Antarctic tourists these days, with excellent opportunities to view several species on an Antarctica cruise, from the raucous abundant colonies of South Georgia’s southern elephant seals and Antarctic fur seals—the most important populations of both species anywhere—to those unforgettable encounters with the big, predatory leopard seals paroling along the Antarctic Peninsula.

You can learn more about the natural history of Antarctic pinnipeds here, and read up on the related—and equally, if not more consequential—industry of Antarctic whaling here.

Disclaimer

Our travel guides are for informational purposes only. While we aim to provide accurate and up-to-date information, Antarctica Cruises makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information in our guides or found by following any link on this site.

Antarctica Cruises cannot and will not accept responsibility for any omissions or inaccuracies, or for any consequences arising therefrom, including any losses, injuries, or damages resulting from the display or use of this information.